For hundreds of years, the Hudson River — called the Muhheakantuck, or “the river that flows both ways,” by the Lenape — was the highway of the valley. From Munsee, Mohawk, and other Indigenous nations’ Mishoon canoes to Dutch sloops, and later to countless schooners, steamers, and other nautical vessels, the River has been essential for travel and livelihoods throughout the eras. Today, the Hudson River is a designated federal marine highway and part of the Great Loop. Its northern boundary is the Great Lakes, its western boundary is the Mississippi, and its southern and eastern boundaries are the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic respectively.

1891 Watson & Co. Maps Collection. ©Haverstraw Brick Museum Archives

River travel today remains scarce. Haverstraw and other settlements on the river have a hard time maintaining what few marinas remain. The river beds are primarily made up of sediment deposits, and to prevent silt erosion requires costly dredging. Moreover, many of these materials also contain PCBs. Individuals and commercial craft have thus shrunk dramatically, and public transport has been confined to the Haverstraw-Ossining ferry.

The Brick Industry and River Shipping

In Haverstraw, the Hudson River played a crucial role in supporting the brick industry. Village docks were The bustling centers of activity as hundreds of millions of bricks were shipped ALONG THE RIVER EACH YEAR. These shipments moved both north and south, connecting Haverstraw’s production with the broader region and making the brick industry a significant part of the area’s economic life.

As the brickyards brought in capital and helped increase the village’s population, some brick manufacturers — like the Peck Family — opened their docks to a growing steamboat dayline industry. By the 1860s.[1]

The Rockland Print Works dock, and especially the Nyack & North River Steamboat Co’s docks, also followed the trend of opening their docks to growing passenger transportation on the river. It would take another two decades for Haverstraw to have its own steamer, which ushered in a new chapter of river travel for the village: The Emeline

Advertisement from the Rockland County Messenger, courtesy of HRVH Newspapers.

The Emeline 1857-1917

The Emeline was built in 1857 as the Mantasket by Thomas Collier in NYC. The steamer was initially used as one of General Ulysses S. Grant’s dispatch boats between Boston and Hingham during the Civil War. Retiring from government service, she was bought by Captain David. C. Woolsey in 1883 and renamed the Emeline.[2] The Woolsey family had already extensively invested themselves into the boating industry, building schooners in the 1800s. John I. Woosley of Haverstraw, for instance, helped build the American Eagle schooner. Once described as the “fastest sloop sailed in Haverstraw Bay,” the name now adorns an American Cruise Line ship.[3]

The purchase of the Emeline was groundbreaking as she was the first steamboat owned in Haverstraw. — disregarding the John Smith and Sadie tugboats used in shipping brick.[4]In the coming year, she began her ferry service, sailing the Hudson with other legendary vessels like the Chrystenah — purchased by Woolsey in 1907, which had its respective route between Nyack and NYC.[5] Woolsey, the Emeline’s captain and co-founder of the Newburgh and Haverstraw Steamboat Company, lived on 10 Front Street. In the winters, Daniel de Noyelles recalled that he overlooked his two docked boats and “could almost superintend the repairs from his front windows.”[6]

Chrystenah Steamboat, Kodachrome slide. Daniel De Noyelles Collection, ©Haverstraw Brick Museum Archives

For the next three and a half decades, THE EMELINE was used for ferry service between Haverstraw and Newburgh.

The Emeline began her days departing from Haverstraw at 7 AM, occasionally stopping at Grassy Point and or Tompkins Cove. She continued to Verplank’s Point and arrived at Peekskill at 8 AM. From here, she stopped at West Point and Cold Spring. Her furthest north stop was Newburgh, arriving at around 10 AM. At 3 pm, she turned south and made the return voyage back to Haverstraw.[7] No matter the decade of service, she “hung on to old steamboat traditions including the tolling of a big bell at sailing time.”[8]

Excursions and Commodities

Haverstraw saw other steamers at its docks. This picture depicts the crew of the Commodore, docked at the Rockland “Print Works Dock.” Kieser Collection, ©Haverstraw Brick Museum Archives.

When not on its ferry line, the Emeline was chartered for various outings. In the Summer, the ship traveled to Manhattan, Harlem, and Bowery Beaches.[9] August 15 was one of the only ‘holidays’ on the brickyards and — after brickworkers worked a day and a half on the 13th and 14th to recoup their wages —many laborers took journeys to “Asbury or Palisades Park” on the Emeline and Crystenah.[10]

The vessel was also annually chartered by the Central Presbyterian Church for excursions to Iona Island.[11] Other churches in the area took part in similar ventures, like those of Tompkins Cove. In the neighboring village’s trip in 1900, the Emeline shipped 300 quarts of Ice Cream, which was reportedly still not enough for the 2,000-strong picnic.[12]

While the Emeline largely profited from its passenger service, it was also a big shipper of commodities; its main shipment was fish. Captain Woolsey sold fish wholesale at Front Street, and what was left was sold on the river, with Woolsey acting “as agent for nearly all the fishermen between Haverstraw and Newburgh.” The main catch tended to be Shad, caught in thousands. Salmon were also prevalent, with one catch in 1893 being 77 ⅜ pounds. Sturgeon, or “Albany Beef,” was also common; a fisherman in the same year caught one great Sturgeon that weighed in at 260 pounds![13] Yet, even within 15 years of these catches, the results of overfishing became overwhelmingly apparent. For example, in 1908, shad catches shrank to an average of under a hundred per day.[14]

The Emeline, The Phoenix of the Hudson River

The Emeline was nothing short of a workhorse, bringing thousands of passengers and commodities up and down the river on both daily service and for special excursions. However, she encountered numerous accidents throughout her tenure. This was so much so that when there was a false report that she sank (again) after a storm in December of 1901, the Rockland County Times wondered, “Why it is that this particular boat is singled out for a report of that kind after every storm on a weekday is hard to tell.”[15]

Her first accident that resulted in her sinking into the river at the Catskills occurred on October 5, 1892, around 8 PM. The ship was carrying 400 passengers from Poughkeepsie to Catskill, with many travelers being firemen heading to the latter’s city’s honorary parade for their profession. At Catskills, she ran on a rock, crushing one of her paddlewheels and leaving “the hull in very bad shape.” Many panicked and jumped overboard; however, everyone ultimately made it to shore safely.[16] On October 12, “after four days of continuous work,” she was raised and tugged to Newburgh for repairs.[17]

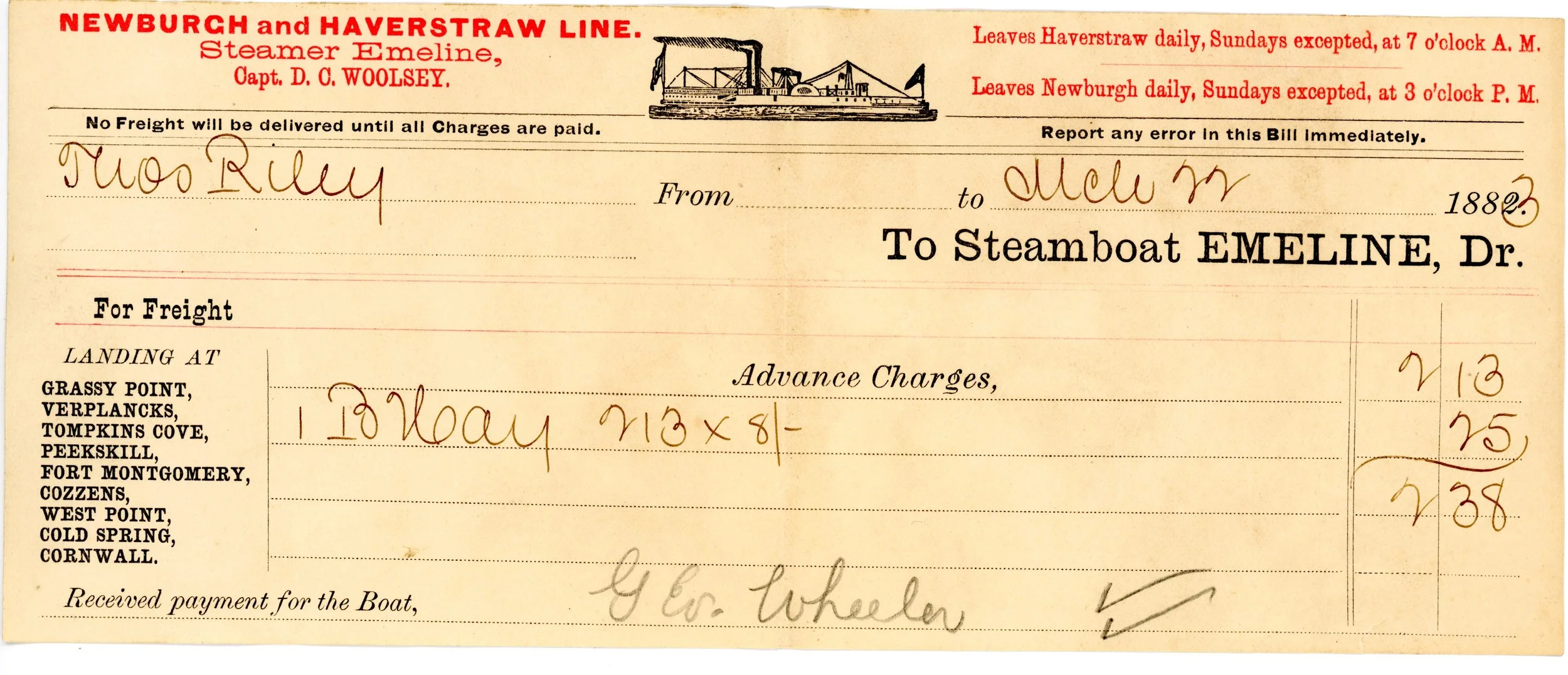

Emeline Steamboat Freight Receipt, Sullivan Collection, ©Haverstraw Brick Museum Archives.

The Hull of a ship is equivalent to a person’s spine — once it is broken, there are far and few methods of repair, and mobility will forever be lost. Thus, the repairmen built “an entire new hull under her,” building what “sailors call[ed] practically a new craft.”[18] After $1,000 repairs, the Emline resumed her normal service within a month on November 11.[19]

On July 11, 1900, around 8 PM, the ship had its second major accident at Newburgh, resulting in her sinking once more. The ship, carrying 800 passengers, attempted to dock at the mid-river city. When the engineer failed to respond to the Captain’s calls to slow the boat and back up, the ship crashed into the pier, and the bow became stuck roughly 20 feet onto land. The crash opened a hole that allowed water to flood in, and by 10 pm, the stern had sunk into the Hudson.[20] Within the following week, she was raised from the water bed for repairs, and by August 25, the ship was running her usual service.[21]

On October 10, 1914, the Emeline was involved in another accident; however, surprisingly, she was not the one to sink this time. In what was described as “one of the thickest fogs that invaded Haverstraw Bay during that season, the Emeline struck the Oneida, a barge carrying cement, which was a part of a larger 5-boat tow pulled by the Canal propeller Aurora. The Emeline was largely without damage, yet the Oneida “went to the bottom like a piece of lead.”[22

The End of the River Travel Age in Haverstraw

Compass salvaged from the Emeline (2007.001.001). The Emeline Collection. ©Haverstraw Brick Museum Archives.

In March of 1917, “the lower river queen” was removed from its ferry service and “confined” to small excursions.[23] In the winter of 1918, the Hudson River froze solid, and on February 7, 1918, the Emeline — whose hull was crushed by the river ice- sank at her dock.

It was then rumored amongst “Haverstraw residents” that Woolsey was “so saddened” about her sinking that it “caused his death.”[24]

Although the ship now rested at the bottom of the Hudson, it would slowly be taken apart. Over the years, “time and persons” stripped the woodwork of the ship.[25] In March of 1921, Captain Willey Burres used scrap lumber from the ship to build “an attractive addition to his property at Second and Middle Streets.”[26] By 1935, the hulk of the ship — its decaying iron skeleton — remained sunken off the shoreline, and would be more of an “eyesore” to many. Having been in the water for nearly two decades, there was concern that little would be able to be salvaged, ensuring that the cost of removal would not be covered.[27]

It would take until March 14, 1951, for the village board to allocate $450 to try to remove the ship’s hull.[28] It did not seem that this worked, as in May of 1954, salvagers who attempted using blast charges to remove the hulk of the ship were ordered to cease operations by Mayor Harry W. Schuler after houses on First Street shook from the explosives.[29] This is the last article found that discusses the fate of the once Queen of the Hudson. Today, the remains of the Emeline rest offshore near the northern end of Emeline Park.

Within the same time frame, river traffic had practically ceased in Haverstraw. In January of 1928, the neighboring village's Nyack Evening Journal reported on the demolition of the old, rotted Crystenah dock, the ship itself being irreparably damaged in 1920, eight years prior. The paper described it as what “mark[ed] the end of river traffic for Haverstraw.”

Moreover, it placed blame partly on “competition furnished by the coming of the automobile.”[30] On June 12, 1929, the adjacent Emeline dock burned down in a fiery, black smoke inducing fire, the ignition presumed to have been started by careless children.[31] In 1938, Peck’s dock remained, but was “little frequented.”[32]

Already by 1954, 12 years after the last brickyard closed in Haverstraw, the Rockland County Times wrote that “the few poles sticking up out of the water hardly tell the world what a busy spot the steamboat docks used to be.”[33] Looking out onto Haverstraw Bay today, the high and low tides still reveal these poles - a lasting remnant of the once booming boating industry.

Reawakening the hudson river highway and preserving the waterway

Haverstraw will never see brick making - an industry that supported river travel to and from the village on a mass scale - ever again. While this industry brought thousands of jobs and countless boats to its shores, clay extraction and the burning of fossil fuels in kilns damaged the surrounding environment. Despite this past, it is possible to both continue an emerging tradition of preserving the riverfront, and to curb fossil fuel usage by promoting river traffic.

In 1931, the Village of Haverstraw purchased the Adler Property and began work on creating the area into a public park. What was once a site pitted between two brickyards is now a place of scenic respite protected by Scenic Hudson. Moreover, it is a part of a wider, three-mile span of largely undeveloped and preserved riverfront, including Bowline and Haverstraw Bay parks.

Although this land remains preserved , the competition of the automobile has continued to displace river travel. With this, fossil fuel emissions have increased. In 2022, automobiles produced 57.18% of travel emissions. Comparatively in the same year, river travel made up a mere 0.80%. [35] While cars are used much more widely, increased group marine travel will help mitigate these emissions.

Revitalizing these piers will benefit not only the environment of Haverstraw and the greater Hudson Valley, but the river-travel economy in the state as a whole.

All Aboard to Haverstraw!

Written by museum historian luke Spaltro. EDITED by rachel whitlow.

CITATIONS

[1] “Day Boat For New York and Albany,” Rhinebeck Gazette, Vol. XII, No. 21, Jun. 26, 1860, 3.https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=idadbhee18600626.1.3&srpos=2&e=-------en-20--1-byDA-txt-txIN-%22pecks+dock%22------

[2] “Emeline Goes to the Bottom,” Rockland County Times, Vol. XXVIII, No. 6, Feb. 9, 1918, 1. https://www.nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=rct19180209-01.1.1&srpos=5&e=-------en-20-rct-1--txt-txIN-%22emeline%22---------

[3] William E. Verplank and Moses W. Colleyer, The Sloops of the Hudson (New York: G. P. Putmam’s & Sons, 1908) 94, 110. https://ia800802.us.archive.org/32/items/sloopsofhudsonhi00verp/sloopsofhudsonhi00verp.pdf

[4] List of Vessels owned in Haverstraw, 1884. Sullivan Collection.

[5] “A.M.C. Smith Line; Old Established Line!” Rockland County Messenger, Vol. XXXIX, No. 15, Aug. 7, 1884, 4. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=rocklandmessenger18840807.2.45.2&srpos=40&e=------188-en-20--21-byDA-txt-txIN-%22emeline%22------ ; George W. Murdock, “Steamer ‘Chrystenah’, 1866-1922,” Kingston Daily Freeman, transcribed by Adam Kaplan, https://www.hrmm.org/history-blog/steamer-chrystenah-1866-1922.

[6] “Haverstraw Items,” Rockland County Times, Vol. XI, No. 45, Jul. 28, 1900, 8.https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=rocklandctytimes19000728.2.36&srpos=17&e=-------en-20-rocklandctytimes-1-byDA-txt-txIN-%22emeline%22------ ; Daniel de Noyelles, Within These Gates (New York: Haverstraw Brick Museum, 2002) 111.

[7] “Emeline Was River Steamer Deluxe in Bygone Days of Hudson Valley,” Rockland County Times, Vol. XLII, No. 45, Nov. 25, 1933, 3.

[8] “Steamer Emeline Ties Up After 34 Years’ Service,” Nyack Evening Star, Mar. 26, 1917. 1. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=jbaggcgi19170326-01.1.1&srpos=221&e=------191-en-20--221-byDA-txt-txIN-%22emeline%22------

[9] “Around Some,” Rockland County Journal, Vol. XXXVII, Aug. 27, 1887, 5. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=rocklandctyjournal18870827.2.37&srpos=73&e=------188-en-20--61-byDA-txt-txIN-%22emeline%22------ ; “The Emeline,” Rockland County Journal, Vol. XXXIX, May 25, 1889, 5.https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=rocklandctyjournal18890525.2.92&srpos=93&e=------188-en-20--81-byDA-txt-txIN-%22emeline%22------

[10] Daniel de Noyelles, “Letters to the Editor,” Rockland County Times, Vol. 73, No. 42, Sep. 6, 1962, 2. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=rocklandctytimes19620906-01.1.2&srpos=10&e=------196-en-20--1-byDA-txt-txIN-%22emeline%22------

[11] de Noyelles, Between These Gates, 146.

[12] “Biggest of the Big,” Rockland County Times, Vol. XI, No. 37, Jun. 2, 1900, 1. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=rocklandctytimes19000602.2.2&srpos=45&e=------190-en-20--41-byDA-txt-txIN-%22emeline%22------

[13] “All Sorts of Fish,” Rockland County Messenger, Vol. XLVIII, No. 2, May 18, 1893, 1. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=rocklandmessenger18930518.2.4&srpos=71&e=------189-en-20--61-byDA-txt-txIN-%22woolsey%22------

[14] “Shad Fishing About Over in Hudson,” Nyack Evening Star, Apr. 25, 1908, 1.

[15] “Saturday’s Big Storm,” Rockland County Times, Vol. XIII, No. 14, Dec. 21, 1901, 1. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=rocklandctytimes19011221.2.9&srpos=233&e=------190-en-20--221-byDA-txt-txIN-%22emeline%22------

[16] “The Emeline Wrecked,” Nyack Evening Journal, Oct. 6, 1892, 1. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=jaaggbbf18921006-01.1.1&srpos=48&e=------189-en-20--41-byDA-txt-txIN-%22emeline%22------

[17] “The Emeline Raised,” Nyack Evening Journal, Oct. 13, 1892, 2. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=jaaggbbf18921013-01.1.2&srpos=51&e=------189-en-20--41-byDA-txt-txIN-%22emeline%22------

[18] “The Emeline To Run Again,” Nyack Evening Star, Nov. 3, 1892, 1. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=jbaggcgi18921103-01.1.1&srpos=56&e=------189-en-20--41-byDA-txt-txIN-%22emeline%22------

[19] “Around Home,” Rockland County Journal, Nov. 12, 1892, 5. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=rocklandctyjournal18921112.2.54&srpos=58&e=------189-en-20--41-byDA-txt-txIN-%22emeline%22------

[20] “Emeline Wrecked,” Rockland County Times, Vol. XI, No. 43, Jul. 14, 1900, 1. https://www.nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=rct19000714-01.1.1&srpos=1&e=-------en-20-rct-1--txt-txIN-%22emeline%22---------

[21] “Haverstraw Items,” Vol. XI, No. 49, Aug. 25, 1900, 8. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=rocklandctytimes19000825.2.88&srpos=19&e=-------en-20-rocklandctytimes-1-byDA-txt-txIN-%22emeline%22------ ; “Raising The Emeline,” Rockland County Times, Vol. XI, No. 44, Jul. 21, 1900, 1. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=rocklandctytimes19000721.2.10&srpos=16&e=-------en-20-rocklandctytimes-1-byDA-txt-txIN-%22emeline%22------

[22] “Emeline Sinks Canal Boat,” Rockland County Times, Vol. XXVI, No. 20, Oct. 10, 1914, 1.

[23] “Passing of the Emeline,” Rockland County Times, Vol. XXVII, No. 12, Mar. 10, 1917, 1. https://www.nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=rct19170310-01.1.1&srpos=7&e=-------en-20-rct-1--txt-txIN-%22emeline%22---------

[24] “Steam Hulk Park Eyesore,” Rockland County Journal News, Feb. 22, 1935, 2. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=ieadbehj19350222.1.2&srpos=6&e=------193-en-20--1--txt-txIN-%22emeline%22+------

[25] Ibid.

[26] “Haverstraw Items,” Rockland County Times, Vol. XXXI, No. 3, Mar. 26, 1921, 8. https://www.nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=rct19210326-01.1.8&srpos=27&e=-------en-20-rct-21--txt-txIN-%22emeline%22---------

[27] “Steam Hulk Park Eyesore,” 2.

[28] “Relief Hose Truck Expected in Six Weeks,” Rockland County Times, Vol. LXIV, No. 18, Mar. 15, 1951, 4. https://www.nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=rct19510315-01.1.4&srpos=21&e=-------en-20-rct-21--txt-txIN-%22emeline%22---------

[29] “Emeline Salvagers Warned on Blasting,” Rockland County Times, Vol. 65, No. 23, May 20, 1954, 2. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=rocklandctytimes19540520-01.1.2&srpos=13&e=------195-en-20--1-byDA-txt-txIN-%22emeline%22------

[30] “Demolition of Old Chrystenah Dock Ends River Traffic For Haverstraw,” Nyack Evening Journal, Vol. 41, No. 20, Jan. 25, 1928, 1. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=jaaggbbf19280125.1.1&srpos=100&e=------192-en-20--81-byDA-txt-txIN-%22emeline%22------

[31] “Fire Destroys Wharf,” Rockland County Times, Vol. XXXIX, No. 16, Jun. 15, 1929, 1. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=rocklandctytimes19290615.1.1&srpos=123&e=------192-en-20--121-byDA-txt-txIN-%22emeline%22------

[32] “Haverstraw Police Seek Owner of Dog Chained to Dock, Left to Starve,” Rockland County Journal News, Vol. 48, No. 291, Apr. 18, 1938, 7. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=ieadbehj19380418.1.7&srpos=40&e=-------en-20--21-byDA-txt-txIN-%22pecks+dock%22------

[33] “The Bank Corner,” Rockland County Times, Vol. 65, No. 17, Apr. 8, 1954, 1, 6. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=rocklandctytimes19540408-01.1.6&srpos=33&e=-------en-20-rocklandctytimes-21--txt-txIN-%22steamboat+dock%22+------

[35] Department of Environmental Conservation, “Energy: 2024 NYS Greenhouse Gas Emissions Report,” 11. https://dec.ny.gov/sites/default/files/2024-12/sr1energynysghgemissionsreport.pdf