Throughout history, the missions of museums and libraries have been intertwined. In Haverstraw, a century divides the founding dates of the King’s Daughters’ Library and the Haverstraw Brick Museum. Yet, both have functioned as institutions that are for the betterment of the public, while at the same time being supported by the public.

Museums and libraries rely heavily on donations of time, money, books, and artifacts. Whether it's an hourly volunteer or a generous financial gift, contributions from everyone, regardless of wealth or status, are vital for these institutions to fulfill their missions. Without these donations, the King’s Daughters’ Society would not have been able to establish the Fowler Memorial Library, which later became essential to the Haverstraw Brick Museum, now in a phase of growth with plans to construct a new building.

The Need for a Haverstraw Library

1906 Illiteracy rates recorded by the New York State Education Department. Documenting only eligible voters excluded many from this survey. Courtesy of

At the start of the 20th century, Rockland County had one of New York's highest illiteracy rates among voters—10%, or 1,129 out of 11,866. This amounted to 100 illiterate people out of every 1,000, or 10% [1]. At this time, illiteracy was defined as not being able to read or write in English. Those most affected were recent immigrants — including Italians, Hungarians, and other Western Europeans—who spoke and wrote their native languages fluently, but who required study and learning to do so in English [2]. In response to these concerns, Haverstraw’s prominent citizens formed the Library and Reading Room Association in 1873. The leadership was composed of men who were either owners of brickyards or deeply invested in the business. [3] While some of the village’s most prominent men led this effort, many of their wives took to utilizing family fortunes in what they saw as charitable efforts. Yet, these were confined to what was deemed acceptable in a patriarchy.

A Sisterhood for the Aid of the Needy, and the Influence of Domesticity in Village Affairs

Photo of Haverstraw High School, Home Economics Class, Circa 1905, Dan DeNoyelles Collection, ©Haverstraw Brick Museum Archives.

In 1891, the “Haverstraw Ladies’ Home Mission Circle” of the Haverstraw King’s Daughters Society was established in the village as a “sewing circle for the benefit of the village poor.” [4] This Circle also gathered aid during Thanksgiving, as well as Christmas time. [5] This included food, clothing, toys, and anything Rockland County Messenger readers “deem[ed] useful to the poor.” However, the organization made a clear distinction of who they saw fit for their charity, describing them as the “worthy poor.” [6]

In 1894, Mrs. William A. Speck was elected president upon the suggestion that the Society devote itself to charity. [7] To do so, they aimed to have “at least one hundred benevolent women of no matter what social position or religious denomination” as members. On January 10, 1895, roughly fifty women partook in its first public meeting held in the village Opera House. In the coming months, a men’s auxiliary branch numbering around forty joined the society. Their only required duty consisted of paying annual dues. Afterwards, the Society agreed upon their working year commencing and concluding in May, and on May 10, a board election was concluded. [8] Shortly after, the women of the Society got to work, establishing a Sewing School with around one hundred students in its first year. [9]

A Library For Those In Need: Fundraising

As the Society expanded its efforts, the wives of brickmakers succeeded their husbands’ efforts in creating a library for the village. On July 8, 1895, Mrs. Everett Fowler, wife of brickyard magnate Denton Fowler Sr., presented a plan to establish a free public library “as a department of the society’s work.” [10] In the same year, the King’s Daughters’ Society began fundraising campaigns towards erecting a building exclusively for the library. [11]

Consistent with domesticity, the Society often held bake sales and included ice cream in the summer. [12] However, they also organized greater endeavors outside of the confines of the home.

Yearly, the Society canvassed the village of Haverstraw for donations. [13] The Daughters also hosted a variety of events, including annual fairs, with a variety of tables where everything from art, baked goods, candies, and canned goods was sold. [14] Occasionally, plays and concerts were assembled at the Opera House, with sales going to the library fund. [15] Many of these ventures were detailed in a "souvenir publication,” which was sold for fundraising. [16]

Moving About the Village

Fundraising, as well as the occasional generous donation, allowed the library to materialize, and on February 15, 1896, the library first opened its doors at Jenkins Hall. [17] Yet, as its collections expanded, the institution quickly began outgrowing its spaces, necessitating to move. In November of 1898, the library moved to the old National Bank Building, located on the corner of Second and Main Street. [18] In April of 1900, they moved to the Old Eagle Hotel. [19] On July 22, 1902, on account of the “insecure condition” of the building they were residing in, they moved their materials to the corner of Main and Rockland Streets. [20]

Gender Divisions Continue

Ladies in the Snow, Circa 1903, Dan DeNoyelles Collection, ©Haverstraw Brick Museum

In the winter of 1896, the women had already amassed a collection of nine hundred books under the library’s stewardship. Moreover, on February 14, 1896, the library was officially admitted to the Regents and the University of the State of New York. [21] Melvin Dewey signed its charter, making it the oldest certified library in Rockland County. [22]

Despite this, the women faced backlash from men in May of 1896 when “the constitution was so amended as to include the library.” In this meeting, the men protested the all-female leadership, forcing the Society to create “a separate paragraph” to require “at least two male” board members. The board of trustees subsequently resigned, and a new board was elected to include two men. [23]

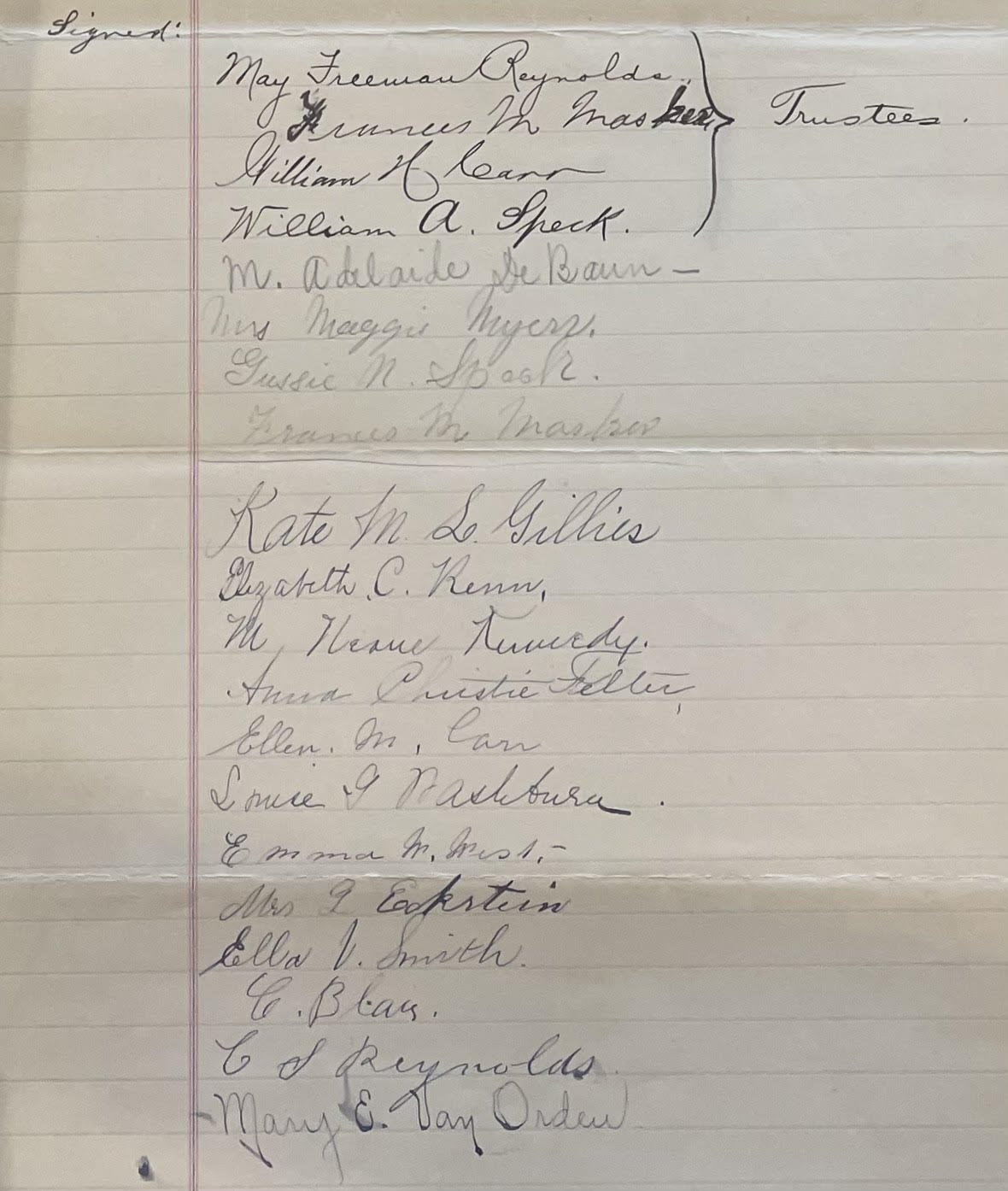

Signatures of the trustees of the King’s Daughters Society, agreeing to the Fowlers’ conditions. Courtesy of HKDPL Local History archives.

It would ultimately take philanthropic donations for the library to materialize. On July 26, 1899, Denton and Katherine E. Fowler made, in their words, a “liberal” $10,000 donation towards the estimated $20,000 construction costs for a new building. The Fowlers’ offer rested on two stipulations: that the Society would match the Fowlers’ donation equally, and have their new home be named the “Fowler” building. The Society collectively agreed and signed with their own first names, rather than with their husbands. [24]

William Parkton was hired as the architect, and in November 1900, the architectural plans for the new building were displayed in the windows of Speck Brothers’ drug store. [25] The building would rest on Front Avenue, overlooking Haverstraw Bay and the Fowler brickyards in the distant south. [26] However, the property on Front Street was increased by $5,000 in December of 1901, and the Society could not afford to purchase the land without a mortgage. [27] It was soon reported that Denton Fowler Sr. had made a “big hitch” about a mortgage, telling the Society he would not put down money for the building if they took one out.

The women of the Society, including its newest president, Mrs. Everett Fowler, tried to meet the men on the middle ground. [28] On December 13, the Society’s Trustees released a statement detailing how they would downsize the building to afford construction without a mortgage. Subsequently, the men of the Society resigned their subscriptions in protest. [29] Despite a loss of subscribers, the new building cost only $11,170. Mrs. Everett Fowler and Mrs. Uriah Washburn both donated another $500, and the Fowlers once again pledged their $10,000 donation. [30]

Fowler brickyard is pictured in the bottom left. The Everett Fowler mansion is pictured across “Fowler’s Gap.” 35mm contact, Sullivan Collection.

The Fowler Building

While the Society credited these women, the extensive profits of their husbands' brickyards also had a large part in the materialization of the building. In 1902, D. Fowler & Son owned 5 machines, 2 barges, and produced 12 million bricks per year. These totals didn’t take into account Fowler’s joint ventures with the Washburns. Washburn, Fowler & Co. owned 12 machines, 4 barges, and produced 25 million bricks per year on their most productive yard alone. [31]

Construction on the new building began and, unsurprisingly, was done with Fowler bricks. [32] By October of 1902, the building’s foundation was [33]completed. Despite having the ability to continue on with construction, the library was still sustained mainly by donations and the efforts of the Society. Moreover, they still did not have the support of the majority of men in Haverstraw, who voted against funding it through taxes. [34] The library attempted to avoid controversy, and “controversial literature [was] excluded” from their shelves, per the Rockland County Times. [35] Still, “a great deal of dissatisfaction ha[d] been expressed by the people” over the building bearing Fowler’s name, as reported by the Times. [36]

In just over six months, the Fowler building was completed. On May 14, 1903, a dedication ceremony was held.

Unfortunately, the location of Trumbell’s original is unknown. However, in 1879, H.B. Hall based his engraving on the original. Courtesy of New York State Archives.

From this date forward, Denton Fowler “relinquished” all control of the building, and the Kings’ Daughter Society remained the sole owner. [37] The library contained three departments on the first floor, including a “Reading Room, Stock Room and Delivery Room,” with the upstairs being reserved for the Daughters’ “society work.” [38] Another room included the Rev. Dr. Amasa Stetson Freeman (1823-1898) memorial room, dedicated to the pastor of the Haverstraw Central Presbyterian Church of over 50 years. His estate donated his religious literature and “relics of interest” to the library. Other material was donated from the clergymen of local “protestants, catholics, and jews,” according to the County Times. [39]

The library also committed itself to the preservation of the county’s history, being described as a “library and museum” by L. Wilson in the Messenger. [40] The Society acknowledged that this history began with “the history of the Aborigines," and aimed to collect “arrow-heads, stone axes, pestles, leather dressing stones,” and other artifacts. They also wished to record the history of the settlers, including “the Hollanders and the English,” by collecting artifacts and papers “stored away in chests and garrets.” [41] Their archive continued into the Revolutionary period, including William A. Speck’s collection of paintings, like John Trumbell’s portrait of Benedict Arnold. [42]

Breaking ground for library’s extension. Original 35mm slide, Dan de Noyelles Collection.

The efforts of the Society gave Haverstonians a great deal of resources to access, with over 10% of villagers now being cardholders. [43] On May 22, the Society's calendar turned to the next working year, and its annual report noted that 3,430 books, including 400 reference books, sat on its shelves. 9,498 books were circulated. [44]

Building a New Museum

On December 5, 1975, a group of prominent North Rockland leaders, descendants of former brickyard owners led by Daniel de Noyelles, and members of the Daughters of the American Revolution, realized a mutual desire to establish a new Museum dedicated to the preservation, study, and celebration of the once brick-making capital of the world. Fundraising included the sales of commemorative bricks. Unfortunately, the economic recessions of the 1970s hindered their efforts.

It took another 20 years for their vision to resurface. On September 19, 1995, 27 Haverstronians convened at the King’s Daughters’ Library to discuss the creation of the Haverstraw Brick Museum.

Afterwards, they immediately began collecting artifacts — including thousands of bricks, papers, ledger pay-books, glass plates, 35mm negatives, furniture, paintings, textiles, and much more related to the North Rockland brickmaking industry.

Absolute Charter for Haverstraw Brick Museum.

On March 11, 1997, the group achieved another milestone when the Museum was granted its temporary charter, and in 2012, its Absolute Charter from the Board of Education by the Board of Regents of the University of the State.

Like the King’s Daughters’ Society, the Museum, its artifacts, and knowledge production roamed throughout the village, occupying a handful of spaces. This included the now-defunct Arts Alliance of Haverstraw, Village Hall, and the front windows of its soon-to-be next-door neighbor, Lucas Candies. It would take until 2002 for the Museum to have a space of its own at 12 Main Street, the site of the former Rosenberg Hardware Store.

Twenty-three years later, and the Museum will once again be looking for a temporary home as the construction of a new, three and a half story building takes place.

This will be a significant undertaking, requiring countless working parts. Every architectural plan, engineering report, executive decision, trustee meeting, as well as every donation of time and money, moves the museum one step closer to its new home.

This new building’s architecture and exhibits will emphasize hands-on STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Architecture/Sculptural Arts, and Math). Through programs such as “Discover the Past, Learn the Future,” the Museum will not only educate the public about the extensive history of Haverstraw and Hudson River brickmaking, but will also allow for contemporary projects with visiting students and researchers in carbon-neutral architecture, 3-D printed brick, and much more.