IN A VILLAGE BUILT BY IMMIGRANTS

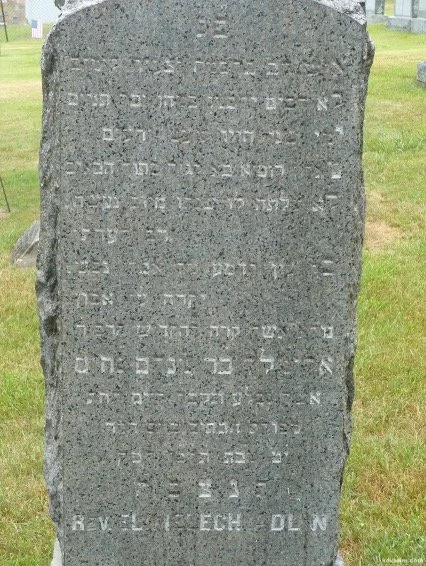

Rabbi Elimelech Adlin’s gravestone in the Sons of Jacob Cemetery. ©Haverstraw Brick Museum Archives.

In the nineteenth century, small Jewish communities flourished in the most unexpected corners of America, from the factory towns of the Hudson Valley to the wind-swept plains of the West. These towns were built by immigrants who brought with them not only their faith, but also their memories of the Old World, both of which influenced their lives in the United States. Among these enclaves was Haverstraw, the brickmaking capital of the world, where industry and faith intertwined. The story of Rabbi Elimelech Adlin, a young immigrant whose life ended in preventable tragedy, offers a window into that moment of fragile permanence: when Jewish life in America was still being built, quite literally, on unstable ground.

Alongside the Mt. Repose Cemetery on Route 9W is a small Jewish cemetery belonging to the Sons of Jacob congregation. Initially seeming insignificant, this Jewish cemetery offers a glimpse into the lives and struggles of the Jews who once called Haverstraw home. A close look reveals stories literally etched into six graves that stand out, each bearing the same date of death: January 8, 1906. One in particular contains a beautifully written acrostic inscription in faded but legible Hebrew, to which nothing is comparable anywhere else in the cemetery. This marker belongs to Rabbi Elimelech Adlin. However, the gravestone itself asks more questions than it answers. What was he doing in Haverstraw in 1906? How did he get there, and who was with him? Who, exactly, was Elimelech Adlin?

The Jews of Bricktown

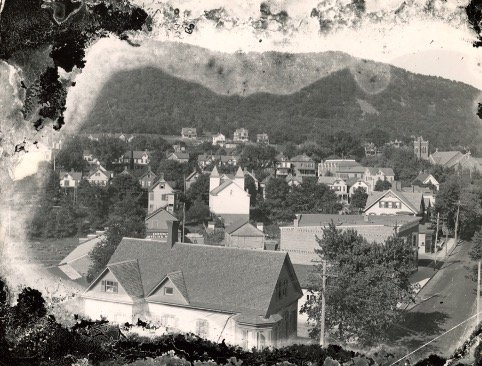

An aerial photograph from 1911 shows the rear of the synagogue; its twin white towers stand out marvelously from the surrounding buildings. ©Haverstraw Brick Museum Archives, Sons of Jacob Collection

Haverstraw’s proximity to New York City and to clay deposits that allowed for the mass manufacturing of bricks resulted in the village becoming home to a large immigrant community, including a sizable Jewish population.

While small per-capita, in early 20th-century Rockland, the largest Jewish centers were the towns of Haverstraw and Nyack. [1] Like other Jewish communities around the world, Haverstraw’s Jewish community stuck together. It is clear from the list of landslide victims that many, if not most, were Jewish. Rockland and Division streets were densely populated with Jewish shop owners and families.

The first evidence of Haverstraw’s Jewish population was recorded in the village on March 5, 1897, when they established a cemetery. [2] Soon after, the community founded the Sons of Jacob congregation, and on August 9, 1899, the congregation filed a certificate of incorporation. [3] On September 3, 1899, the community dedicated its synagogue building [4], which was funded with a $2,000 loan from Michael McCabe, a local banker, politician, and publisher of the Rockland County Times. [5]

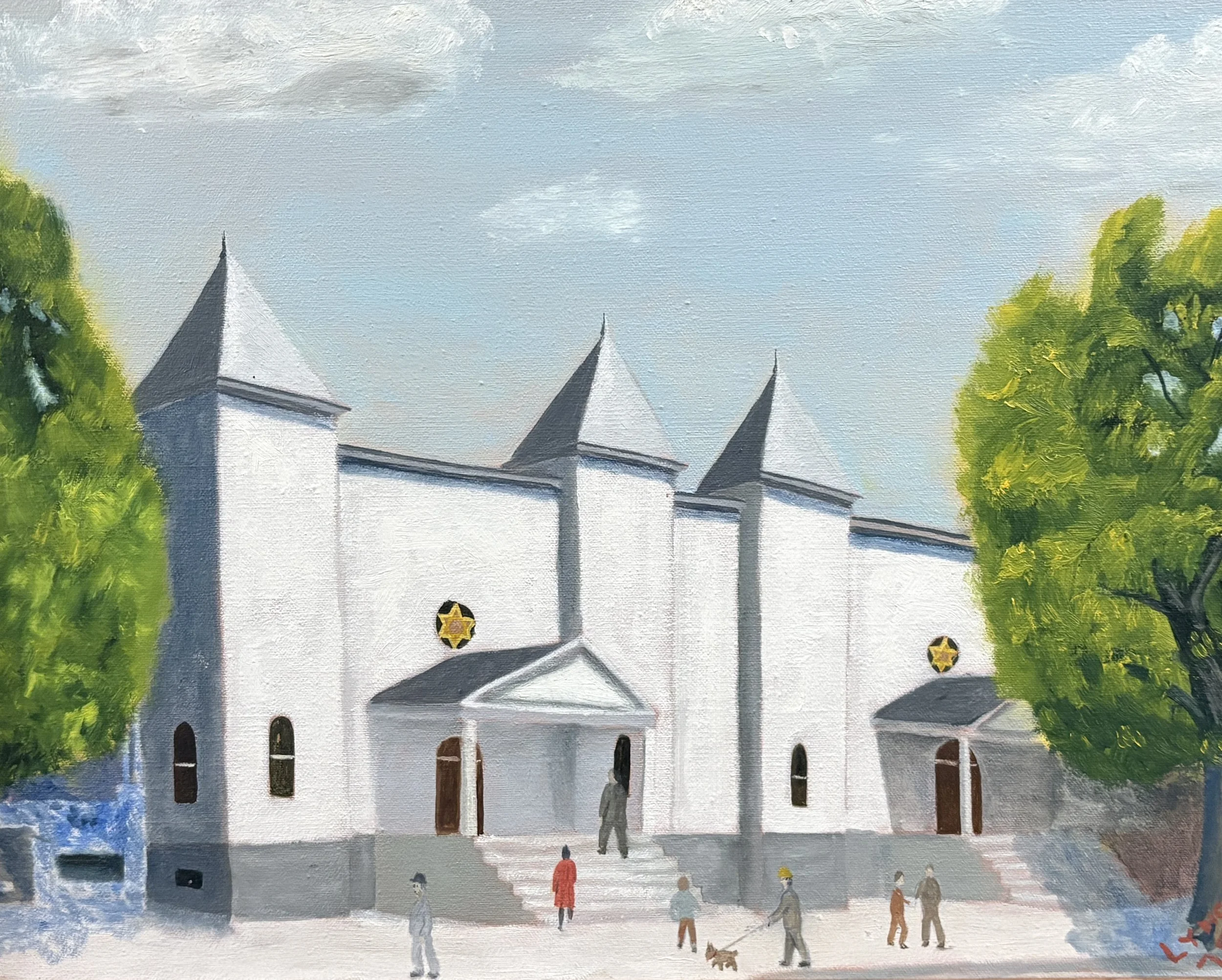

1975 painting of the Sons of Jacob Synagogue following a renovation and expansion. Sons of Jacob Collection, ©Haverstraw Brick Museum Archives

The first time the synagogue appears on a Sanborn insurance map is in 1903, at approximately the same location as the Sons of Jacob building stands today. The synagogue was a testament to the congregation's dedication and hard work. Although the Haverstraw community was small and composed mostly of shopkeepers, small business owners, and laborers, according to paintings in the Museum archives, the synagogue itself was built on a grand scale.

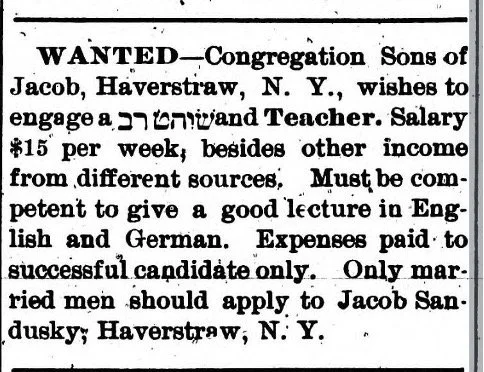

In 1903, the community placed ads in Jewish newspapers in Manhattan, looking for a Rabbi willing to move himself up the Hudson River to Haverstraw, where he would serve the Congregation in this newly constructed synagogue. Adlin — educated in a yeshiva, somewhat fluent in English, and in a new country, eager to make a living — probably saw one of these advertisements, and applied.

He was soon hired by the Congregation to serve as their Rabbi, Shochet (ritual slaughterer), and teacher. [6] In the Brooklyn Eagle’s eulogy of Adlin, it is stated that “He took up his residence in Haverstraw and soon became well-known and universally esteemed.” [7]

Advertisement by the Congregation Sons of Jacob in The Hebrew Standard, 27 February 1903. Accessed via Historical Jewish Press

The Adlin Family

Born in the Russian Empire in either 1885 or 1887 to Menachem Nachum and Rebecca Leah Adlin, Elimelech Adlin fled Mahilyow, modern-day Belarus, a city that had a majority Jewish population. [8] The young Elimelech would have been at risk of being conscripted into the Russo-Japanese War, which started in February 1904, and in the same year, the Jews of Mahilyow faced a pogrom. [9]

It is unclear how old Elimelech was when he fled, or exactly when he was born. According to the record at Ellis Island, he immigrated on April 12, 1905, and was 18. [10] However, according to a eulogy published for him, he was 20 when he immigrated. [11]

New York marriage records reveal his marriage to Minnie Medwinsky in Manhattan on Wednesday, June 14, 1905. [12,13] When they got married, Elimelech resided in Haverstraw, while Minnie still lived in Manhattan with her parents. Within a week, Minnie joined her husband in Haverstraw. [14] Elimelech was paid $20 per week, enough that they could live relatively comfortably.

Rabbi Elimelech Adlin. Sons of Jacob Collection, ©Haverstraw Brick Museum Archives

Unlike her husband, Minnie’s life is documented only in official sources, including the 1900 and 1910 censuses, as well as her series of testimonies in court. There is no known picture, memoir, biography, or obituary for her. Therefore, tracing Minnie Adlin’s life is difficult.

Minnie Adlin was born in the Russian Empire between 1884 and 1888. She claimed that in 1905, she was about 18 and had been in the United States for eight years. This would put her birth in 1887 and her immigration in 1897. Her native language was Yiddish, and she was also fluent in Russian. [15] She spoke English, but it is unclear how well. Whether she could read and write is also unknown. Based on Minnie’s testimony, it is evident that Rabbi Adlin spoke English well. [16]

Photo of the Landslide, circa 1906, Thomas Sullivan Collection, ©Haverstraw Brick Museum Archives

The Great Haverstraw Landslide

As the brick making industry expanded, companies needed to find new ways to extract clay. Oftentimes engaging in unsafe and risky practices, many took to undermining. [17] As a result, landslides became a problem in Haverstraw. In 1898, a crack opened in the street, and a landslide “several hundred feet in length” occurred near Mrs. Mary T. Finegan’s house. [18] Being the daughter of the New York State Assemblyman Thomas Finegan, Mary had the resources available and sued the Eckerson Brick Company, claiming that their excavations threatened her property. [19] Likewise, on June 14, 1902, the Rockland County Times reported that another large crack had opened on Rockland Street, and that residents of the area were prepared to evacuate at a moment's notice. [20]

Photo of the Landslide, circa 1906, Thomas Sullivan Collection, ©Haverstraw Brick Museum Archives

January 8, 1906, would become a day that defined Haverstraw for generations. That morning, a large crack in the street had widened significantly. Since cracks in the street were common, the day continued as any OTHER did. As the sun set, flurries started to fall, leaving a fresh coating of snow on roofs and the streets.

Later that night, a series of three landslides occurred between 11 p.m. and 11:35 p.m. Most of the victims were killed in the first landslide. Others were killed when they tried to retrieve their belongings from houses and stores that were in peril, only to be swept away in the second and third slides. Oil lamps and wood-burning stoves in the houses set the wreckage ablaze.

The only thing that stopped the whole town from going up in flames was the fresh layer of snow that had recently fallen, which acted as a barrier between the embers and the wooden structures in the area. The cold, however, was a double-edged sword as fire hydrants froze, water mains burst, and the firefighters could not effectively perform their duties. In total, at least 19 people were killed, and 13 buildings were swept away.

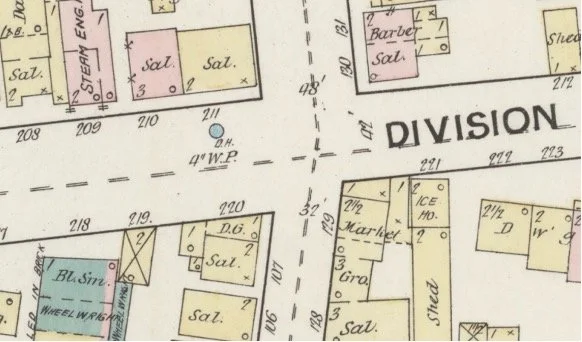

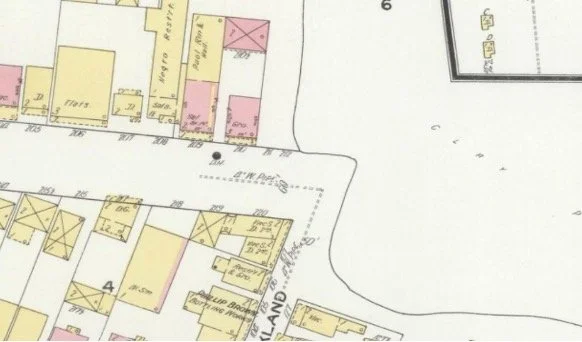

Using Minnie’s court testimonies and the Sanborn insurance maps, the location of the Adlins’ apartment can be identified at 36 Division Street, which was not destroyed in the landslide. [21]

On January 14, the body of Rabbi Adlin was found, reportedly interlocked with the body of Haskel Nelson, a congregant Adlin was trying to save. [22] Rabbi Adlin’s wife Minnie was expecting their first child, and six months later she gave birth to a baby boy, Max, while living with her parents in Manhattan. [23] The date of Rabbi Adlin's death would officially be January 8, 1906; the 19th of the Hebrew month of Tevet. After Rabbi Adllin’s body was found, there was a service for him at the synagogue followed by an English service at the opera house. [24]

Legal Fallout and Newspaper Reporting

1903 Sanborn Fire Insurance Co. map showing the intersection of Rockland and Division streets. the Adlins lived at the house on parcel 219. From the Library of Congress

In 1908, Minnie Adlin would be the first of a handful of survivors or relatives of victims of the landslide to sue either the town or the brick makers. Minnie Adlin, as the Rockland County Times described it, “Trying to get simple justice, trying to get an unbiased hearing on her claim, friendless and alone” [25] , faced countless injustices, corruption, and delays until she ultimately walked away with nothing to show for it.

1910 Sanborn Fire Insurance Co. map showing the northern and eastern sections of Rockland and Division Streets destroyed by the landslide. From the Library of Congress

The Rockland County Journal reported rather candidly and truthfully on the lawsuits brought by Minnie Adlin and others. The Journal noted that Adlin was seeking $25,000 in damages against a slew of brick makers, and she was suing using a law firm from Brooklyn. [26] The Journal also reported that Judge Maddox of the New York Supreme Court in Brooklyn sided in favor of the defendants, against Adlin, but, to avoid undue hardship on the widow, ordered that the defendants pay the cost to print the case, which was expensive. [27]

Different Rockland newspapers reported on the landslide and later lawsuits with varying biases. The wording of the Rockland County Times article shows that the publisher sided with Adlin and felt the injustices she had to face: “The Times has no comment to make except to enumerate the peculiar and singular instances of what a poor litigant must suffer who braves a wealthy corporation and attempts to get anything like a fair deal or an honest, unbiased hearing of his or her claim.” [28] The Times continues to make polite yet firm statements as it addresses those who claimed that the judges and courts were overworked, saying: “We respectfully suggest, if we had any power to suggest, that this poor Jew woman ought to be at least given something like decent treatment.” [29]

Other newspapers, specifically those not in Haverstraw, also blamed the brickmakers. However, they still gave them the benefit of the doubt. The Nyack Rockland County Journal reported, “The fall of the cliff appears to have been due wholly to the gradual (sic) undermining of the brickmakers.” [30] The paper still tried to give them room to rectify their actions, claiming they would “give all possible aid.” [31]

Despite the supposed grace of the brickmakers, Minnie’s repeated efforts at a lawsuit were in vain. The brick maker’s case was that, by running into the Nelson’s store, which was on the brink of collapse, Rabbi Adlin put his own life in danger and, because of that, they were not liable for his death. [32] Minnie Adlin’s English-speaking ability was called into question throughout the trial. She could at least speak English, but whether she could read or write is unclear. [33] Ultimately, in 1911, the Journal reported that Minnie Adlin was defeated in her efforts by Judge Scudder. [34]

TODAY

Over the decades, the Sons of Jacob synagogue was renovated and expanded, eventually doubling in size. Tragically, the original building burned down in 1966, shortly after being renovated. As it had done before, the community rebuilt. The new synagogue they built, which stands today in the same spot on Clove Avenue, served the Sons of Jacob synagogue until it shut its doors in 2020.

Rabbi Elimelech Adlin, the man whose tombstone asked more questions than it answered, was not in Haverstraw long enough to leave a mark on the village, but Adlin’s story remains in memory and oral history, even as Haverstraw’s Jewish population gradually dispersed. What remains is Adlin’s gravestone, its acrostic inscription still legible amid the quiet rows of the Sons of Jacob Cemetery, anchoring his presence in local history. Today, through the work of the Haverstraw Brick Museum, his name has not been allowed to be forgotten, rejoining him to the narrative of a community that once was. January 8th, 2026, will be the 120th anniversary of the Haverstraw Landslide, and it will also be the 120th anniversary of Rabbi Elimelech Adlin’s death on the 19th of Tevet. Join us in remembering and commemorating the tragic landslide.

Written by Ezra Ratner

Sources

[1] There is a longstanding debate within Rockland County as to which Jewish population is older. Haverstraw’s Sons of Jacob was incorporated in 1899 (although it is claimed that the community had existed as early as 1877), while Nyack’s Sons of Israel was founded in 1870; however, it seems that Jews had lived in Haverstraw without an organized congregation for longer.

[2] Certificate of Incorporation - Cemetery of Congregation Sons of Jacob, HD03-00000065. 1897. Rockland County Court Records.

[3] Certificate of Incorporation - Congregation Sons of Jacob Haverstraw, HD04-00000034. 1899. Rockland County Court Records.

[4] The American Jewish Yearbook. New Synagogues Dedicated in the United States during 5660. Vol. 2. N.p.: American Jewish Committee. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23600177.

[5] Fried, Yitzy. 2022. “Monsey Memories: Sons of Jacob, "The First Synagogue in Rockland."” Rockland Daily.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Author Unknown. 1906. “22 Lives Lost in Landslide.” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (New York, NY), January 9, 1906, 1.

[8] Yad Vashem. n.d. “Early History of the Mogilev Jews.” yadvashem.org. https://www.yadvashem.org/education/educational-materials/lesson-plans/mogilev/history-of-jews-in-mogilev.html.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Statue of Liberty - Ellis Island Foundation. n.d. Passenger Record for Meyer Edlin, arriving April 12, 1905, on the Potsdam. New York, New York: n.p. https://heritage.statueofliberty.org/passenger-details/czoxMjoiMTAyMzgzMDUwMjYxIjs=/czo0OiJzaGlwIjs=#passengerListAnchor.

[11] Zvirin, Nathan. 1906. “Robbery That Leads to Murder: How the Earth Swallowed Up Jewish Families in Haverstraw.” Yiddishes Taggeblatt (New York, NY), January 10, 1906, 1. https://www.nli.org.il/en/newspapers/ytb/1906/01/10/01/article/2/?e=-------en-20--1--img-txIN%7ctxTI--------------1#.

[12] Following the Orthodox Jewish practice of getting married on Tuesday evenings, the Adlins were married legally on Wednesday, June 14, 1905, but presumably had a Jewish ceremony the night before, Tuesday, June 13.

[13] Ancestry Operations Inc. n.d. “New York, New York, U.S., Extracted Marriage Index, 1866-1937.” Ancestry.com. http://ancestry.com.

[14] Adlin v. Excelsior Brick Co., 129 App. Div. 713, 113 N.Y.S. 1017 (N.Y. App. Div. 1908). p. 30

[15] Adlin v. Excelsior Brick Co. of Haverstraw, 151 App. Div. 892 (N.Y. App. Div. 1912). p. 55

[16] “My husband understood English… he understood it well.” Ada (Silverman) DeCheflin, a neighbor, said regarding Minnie’s testimony: “She testified it wrong, she doesn’t understand English well enough.” Adlin v. Excelsior Brick Co. of Haverstraw, 151 App. Div. 892 (N.Y. App. Div. 1912) p. 55

[18] Nyack Evening Star. 1898. “A landslide.” May 18, 1898. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=jbaggcgi18980518-01.1.1&srpos=33&e=-------en-20--21--txt-txIN-%22landslide%22+clay+haverstraw------.

[19] Rockland County Times. 1921. “Former Assemblyman Thomas Finegan Dies Early Tuesday Morning Following Fatal Heart Failure Attack.” Rockland County Times Weekly (Haverstraw), August 13, 1921.

[20] Rockland County Times. 1902. “Street is Cracked.” June 14, 1902. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=rocklandctytimes19020614.2.6&srpos=2&e=------190-en-20--1-byDA-txt-txIN-%22rockland+street%22----1902--.

[21] Minnie’s testimony reads that her and her husband lived “on Division Street near Rockland (street)… on the south side of Division Street as you face the Hudson River about two houses from the corner… west of Rockland Street.” Adlin v. Excelsior Brick Co., 129 App. Div. 713, 113 N.Y.S. 1017 (N.Y. App. Div. 1908) p. 22

[22] In her testimony in court, Minnie Adlin initially says that she had not heard that her husband had been found inside the Nelson’s store, which would prove that he had put himself in danger. Later on, she claims that the story is false and denies that Elimelech ever ran into Mr. Nelson’s store..

[23] Max would spell his last name “Edlin”, his Hebrew name was Elimelech ben (son of) Elimelech, notable due to the Ashkenazi Jewish custom of not naming children after living relatives.

[24] Rockland County Journal. 1906. “Many Visited Haverstraw.” Rockland County Journal (Nyack), January 20, 1906. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=cl&cl=CL2.1906.01&sp=rocklandctyjournal&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN-------.

[25] Rockland County Times. 1908. “Another Mis-trial?” The Rockland County Times (Haverstraw, NY), February 22, 1908, 1. https://nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=rct19080222-01.1.1&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN----------.

[26] The Rockland County Journal. 1906. “Widow Seeks Heavy Damages.” The Rockland County Journal (Nyack), February 24, 1906. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=cl&cl=CL2.1906.01&sp=rocklandctyjournal&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN------

[27] The Rockland County Journal. 1908. “Haverstraw in Luck.” The Rockland County Journal (Nyack), April 25, 1908. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=cl&cl=CL2.1906.01&sp=rocklandctyjournal&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN-------.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Adlin v. Excelsior Brick Co. of Haverstraw, 151 App. Div. 892 (N.Y. App. Div. 1912). p. 106

[33] 1900 United States Federal Census. 1900. Manhattan, New York, New York: n.p.

[34] The Rockland County Journal. 1911. “Widow Loses Suit.” The Rockland County Journal (Nyack), May 6, 1911. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=cl&cl=CL2.1906.01&sp=rocklandctyjournal&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN-------.